Abstract: Prosthodontic rehabilitation of patients undergoing ablative cancer procedures involves significant challenges and technicalities in the construction of a prosthesis like repeated prosthetic adjustments or remakes, and ultimately improving quality of life. Mandibular resection causes the mandible to deviate towards the defect, which causes loss of occlusion on the non-resected side, altered mandibular movements, cosmetic deformity, difficulty in swallowing, and impaired speech and articulation. Restoring speech, deglutition, mastication, and respiration in individuals who have undergone maxillary resection involving the maxillae, hard and soft palates, and paranasal sinuses is extremely difficult. It may not be feasible to surgically reconstruct in each case. In conjunction with physical therapy, prosthetic rehabilitation assists such patients in regaining form and function and improving their quality of life. It can be achieved by using obturators and mandibular guidance prosthesis, which could efficiently retrain the maxilla and mandible following surgical procedures to achieve a functional occlusal relation, enabling early progression leading to a permanent restoration that functions almost perfectly. This review’s objective is to highlight the various rehabilitative prosthesis that can be used to correct maxillary insufficiency and mandibular discontinuity defects following tumour resections using the available information.

Key words: rehabilitation, prosthesis, maxillofacial defects

The goal of oral rehabilitation in hemimandibulectomy patients is to prevent altered mandibular movements, disfigurement, swallowing

difficulty, impaired speech and articulation, and

mandibular deviation towards the resected site.

Various prosthetic options, such as maxillomandibular fixation, implant-supported prosthesis,

removable mandibular guide flange prosthesis, and palatal ramp restoration, can help achieve

this. A provisional appliance, such as a mandibular guide flange or palatal ramp prosthesis,

can be constructed to restore a normal maxilla-mandibular relationship.1

The maxillary sinus is the largest of the paranasal

sinuses and has the highest incidence of malignant sinus tumours. 20% of paranasal sinus cancers are in the ethmoid sinus, 80% in the antrum,

and less than 1% in the sphenoid and frontal sinus.2

One of the most difficult aspects of oral and

maxillofacial reconstruction is the reconstruction

of maxillary bone defects caused by pathological or congenital causes. The primary goal of

these reconstructive efforts is to protect and improve the patient’s quality of life by attempting

to restore the patient’s lost form and function.3

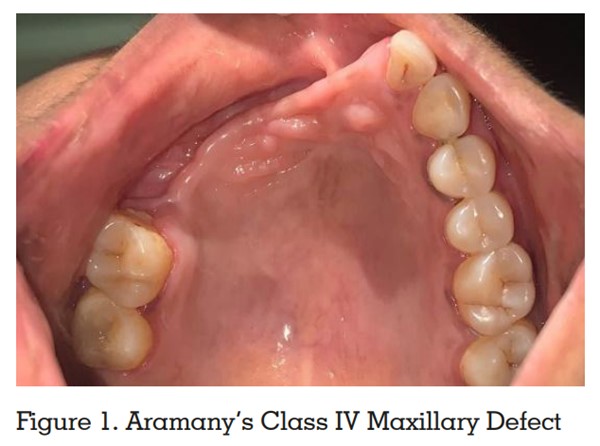

Maxillary neoplasms are commonly treated by

surgical resection of the maxilla and adjoining

structures (maxillectomy). The surgery often results in abnormal communication between the

oral and nasal cavities. The functional and aesthetic rehabilitation of these resected maxillary

deformities is a complicated task. The midfacial region is dominated by the maxillae, which

also contribute to important midfacial structures

such as the orbit, zygomaticomaxillary complex,

nasal unit, and stomatognathic complex.4 Prosthetic obturation’s main objectives include separating the oral cavity from the sinonasal cavities and closing the maxillectomy defects to prevent

regurgitation.5

Prosthetic measures at differing

stages assist patients in regaining aesthetic and

functional abilities. An effective obturator prosthesis enhances speech, mastication, swallowing, and aesthetics.6

Tumors may arise in the alveolar mucosa, in the

periosteum and bone of the mandible, or from

the dental elements requiring segmental or radical resection of the mandible. Squamous cell

carcinoma of the alveolar mucosa, ameloblastoma, and osseous sarcomas are prevalent among

these lesions.

Ameloblastoma is a rare odontogenic tumor

that tends to be locally invasive. It occurs in the

mandible 4 times more frequently than in the

maxilla. Although midline lesions have been described, ameloblastoma of the mandible often

appears as an indolent mass in the third molar

area. It is most prevalent during the 3rd and 4th

decades of life. Males and females are approximately equally affected.

About 10% of all oral cancers are Squamous cell

carcinomas of the gingiva and alveolar mucosa.

These carcinomas occur more frequently in the

mandible and the molar region is primarily affected. They occur more commonly in men than

in females (4:1). A 25.9% prevalence of HPV-associated head and neck squamous cell carcinoma

(HNSCC) was concluded through a systematic

review. In comparison to oral (23.5%) and laryngeal (24.0%) SCC, the prevalence of oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC) was

higher (35.6%).9

The majority of these tumours

develop in edentulous regions. Tumors often

spread to the floor of the mouth and the buccal

mucosa. Approximately 30% of patients initially

have regional metastasis, which first affects the

submandibular nodes. Squamous cell carcinoma of the mandibular alveolar ridge is primarily

treated surgically, with a marginal mandibular

resection in early lesions and a segmental resection in advanced lesions with extensive bony involvement. Squamous cell carcinoma of the

mandibular alveolar ridge is primarily treated

surgically, with a marginal mandibular resection

in early lesions and a segmental resection in advanced lesions with extensive bony involvement.

The remaining mandibular segment deviates toward the defect after a segmental or hemi mandibulectomy for squamous cell carcinoma, and

the mandibular occlusal plane rotates inferiorly.

Due to the loss of the tissue which controls the

mandibular movements, the deviation occurs.10

Osteosarcoma is the most frequent primary osseous malignancy, which involves the mandible

or maxilla 6 to 7% of the time. The most common

sites of involvement in the mandible are the premolar and molar regions, followed by the symphysis, angle, and ramus. A diffuse swelling or a

palpable, occasionally painful mass is the most

typical sign of osteosarcoma of the mandible. Involvement of the inferior alveolar nerve frequently causes paresthesia of the chin or lip. It typically takes 3 to 4 months for symptoms to manifest

before a diagnosis is made. Osteosarcoma presents as a destructive, ill-defined intraosseous lesion with or without an adjacent soft tissue mass

on radiographic examination.

In hemimandibulectomy, the mandible deviates

due to its loss of continuity, which further results

in aberrant muscle function and facial asymmetry resulting in aesthetic deformities, functional

impairment, and psychological consequences.9

At the vertical dimension of rest, the residual

mandibular segment retrudes and deviates towards the surgical side in patients who have had

a mandibular resection.

Mandibular guidance prosthesis

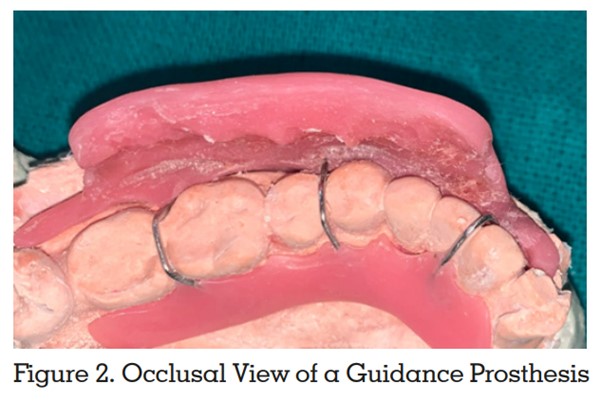

A palatal- or mandibular-based guiding prosthesis can be used for prosthetic rehabilitation

to achieve adequate occlusal function in such

patients.10 A mandibular removable partial denture is affixed to the guide flange on the non-resected side of a mandibular guiding prosthesis

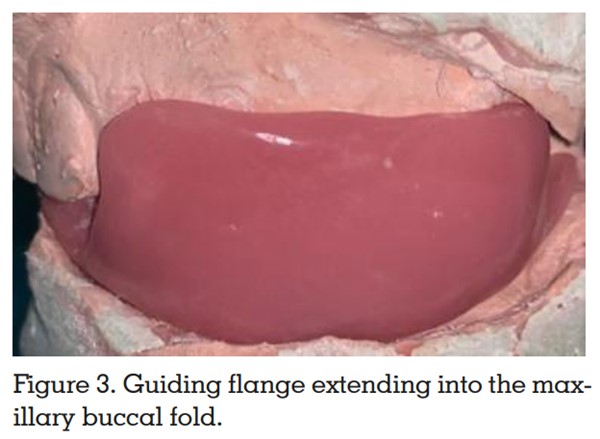

as shown in (Figure 2). By extending the flange

into the maxillary buccal fold, the remaining

mandibular segment is guided superiorly and

laterally to the desired jaw relationship which

can be seen in (Figure 3).11 “The flange mechanically holds the remaining mandible with

minimal to no lateral movement in the proper

position for the vertical chewing stroke.”12-14 This

extension can be made of acrylic resin, cast in

RPD metal, or wrapped in a thick wire loop.13–19

Although acrylic flanges can be adjusted in the

mouth, they are not rigid and are prone to abrasion, so they need to be reinforced with metal or

additional thickness. Metal flanges can be thin

and rigid, causing no distortion or abrasion of

the cheek space. For metal, however, the angle

and length must be predicted prior to casting because metal cannot be adjusted once it is inside

the patient’s mouth. The flange should be “extended 7 to 10 mm from the mandibular RPD in a

superior and diagonal position, shorter than the

maxillary vestibular depth.”12-14 More specialized techniques for determining the flange angulation are now required due to individual variations in the maxillo-mandibular relationship,

mandibular deviation in terms of degree, muscle

potency, and the ability to orient the lower jaw towards the non-resected side. Various guidance

prosthesis can be used to accomplish this. Mandibular guidance prostheses are broadly classified into two types:

Maxillary inclined plane prosthesis

On the non-defect side, palatal to the maxillary

teeth, a functionally generated occlusal record is

used and an occlusal table is fabricated which

slopes away from the natural teeth occlusally.

Interproximal ball clasps or Adams clasps are

used to retain the prosthesis. Due to the residual mandible’s medial deviation, mandibular

closure causes the remaining mandibular teeth

to gradually slide up the incline in a superior

and lateral position until the occlusal contact is

made. The extent of the deviation determines the

duration of wear. Positioning prosthesis with palatal flange can be used in patients who can use

their pre-surgical intercuspal position after mandibular resection with complaints of inability to

prevent the mandible from deviating towards

the defect side during sleep. They struggle to

reestablish their normal occlusal contact after

waking up. Additionally, TMJ discomfort and

muscular ache are frequent problems. To reduce the nocturnal deviation, a palatal flange can be

extended inferiorly into the lingual vestibule between the lateral border of the tongue and the

lingual surface of the remaining mandible. This

flange can be constructed using auto-polymerizing acrylic resin. The palatal extension should

be adequate even when the mouth is open to

prevent medial deviation of the unresected jaw.

The flange shouldn’t impinge on the mandibular

lingual mucosa and should only make contact

with the lingual surfaces of the teeth when the

jaw is opening and closing.20

Intermaxillary fixation

For five to seven weeks, Aramany and Myers

recommended using intermaxillary fixation with

arch bars and elastics following surgical resection. The remaining mandible is retained in its

ideal maxillomandibular position, enabling scar

formation while the defect heals and the teeth

are in occlusion. In the immediate postoperative period, little to no muscle retraining may be

necessary with the use of intermaxillary fixation.

The amount of deviation appears to be inversely

related to how long the mandible is fixated.21, 22

Vacuum-formed PVC splints

This framework comprises upper and lower

splints which are fabricated using upper and

lower plaster models. The upper splint encompasses the palatal vault and all standing teeth

to provide the greatest amount of lateral stability. The vestibular flanges and teeth, which will

serve as the mandible’s closure guiding planes,

should be included in the lower splint. At the

intercuspal position, both the upper and lower

models are articulated. Both upper and lower

splints are then incorporated into the arches

and joined together by adding another layer of

heated polymer between them. Flanges and indentations on the lower part of the splint make

it simple to place the mandible and lower teeth

in the right occlusal relationship when the jaws

are closed. Since it is comfortable for the patient

to wear, the plastic splint effectively controls and gently restrains jaw motions. The patient may

also wear the apartment at night. Once the patient has been accustomed to the path of closure,

this appliance must be replaced by a more definite acrylic or metal appliance.15

Exercise program

To retrain the residual muscles, enhance the

maxillo-mandibular relation, minimize scar contracture, and reduce trismus, prosthetic treatment should be accompanied by a planned exercise program.23

Two weeks following surgery, the exercise regimen can commence. Simple mandibular opening and closing with and without the appliance

are performed, as well as the patient grabbing

the chin and repositioning the mandible away

from the surgery site.24

Maxillary obturators

Maxilla is the site of the majority of intraoral abnormalities, in the form of an opening into the

antrum and nasopharynx. The hard and soft

palates, alveolar ridges, and floor of the nasal

cavity may all be involved, or the opening may

be extremely small. Postoperative maxillary abnormalities predispose the patient to hypernasal

speech, nasal cavity fluid leakage, and compromised masticatory function.25

A maxillary obturator is used to repair the intraoral defects. In cases of partial or complete

maxillectomy, an obturator (Latin: obturare, to

stop up) is fabricated.25 Prosthetic rehabilitation

goals for total and partial maxillectomy patients

include separation of the oral and nasal cavities to allow adequate deglutition and articulation, possible support of the orbital contents to

prevent enophthalmos and diplopia, soft tissue

support to restore the midfacial contour, and an

acceptable aesthetic result.26 The following are

the indications for using an obturator::

A typical maxillectomy resection removes the

teeth and alveolar bone along the midline. Desjardins advocated for maintaining the alveolar

bone around teeth that were proximal to the defect.28

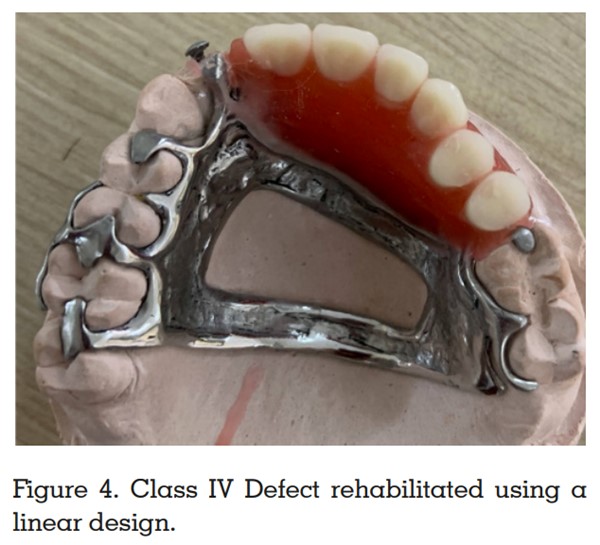

Either linear or tripodal design can be fabricated. Support is attained from the central incisor

and the most posterior abutment tooth while two

or three anterior teeth can be splinted, if possible. By placing a rest on the canine or the first

premolar’s distal surface in a tripodal configuration, the notion of efficient indirect retention is

applied when the dental arch is curved. Either

an I-bar on the central incisor or the labial surface of the anterior teeth with a gate design enables direct retention. The buccal surface of the

molars is used for posterior retention, while the

bracing is situated palatally. If the anterior teeth

are not incorporated into the design, a linear design is indicated.2

The premaxilla on the side with the defect is preserved. The bilateral design resembles a Kennedy Class II removable partial denture. In this

case, the tripodal design is indicated. It is advised to splint the two teeth located proximall the defect. The tooth closest to the defect and the

most posterior molar on the opposing side are

used for the primary support. The fulcrum line

and an indirect retainer are positioned as perpendicularly as possible. On the distal surfaces of the molar and the anterior tooth, guiding

planes are situated proximally. On all abutment

teeth, the buccal surfaces serve as the site for

retention, and the palatal surfaces serve as the

location for stabilizing components.29

The entire dentition is preserved, and the defect

is located in the center of the palate. It is constructed using a quadrilateral design. Premolars

and molars are used to provide support. The

buccal surfaces provide retention, while the palatal surfaces provide stability.29

On the nonsurgerized side, the defect encompasses the premaxilla. A Linear design is recommended. All remaining teeth have support in the

middle, as seen in (Figure 4). On the premolars

and molars, respectively, retention is seen mesially and palatally. On the palatal surface of the

premolars and the buccal surface of the molars,

stabilizing components are attached.29

The hard palate, portions of the soft palate, and

the posterior teeth are resected while the anterior teeth are preserved. Two terminal abutment

teeth are advised to splint on each side. The

palatal surface of the most distal teeth provides

stability and support, while I-bar clasps are positioned bilaterally on their buccal surfaces. This

arrangement is basically tripodal. A gate prosthesis could also be fabricated in such cases as

an alternative.29

The least common class of anterior palatal defects is generally caused by trauma rather than

surgery. Such defects involve the bilateral splinting of two anterior teeth and they are joined together by a transverse splint bar. A quadrilateral

design is fabricated in case of a large defect or

when the remaining teeth have a poor prognosis.29

Due to the patient’s advanced age and the severity of the defect, rehabilitation for these patients continues to be an enormous challenge.

Numerous challenges associated with surgery

and prosthetic rehabilitation like lack of maxillary bone including pterygoid plates sometimes

zygomatic bone involvement, loss of lip support,

adherence of nasal and sinus mucosa with palatal mucosa, fibrosed palatal mucosa, lack of vertical guidance, reduced stress-bearing area, and

over closure of mandible need to be addressed.

Establishing normal function with low morbidity

and long-term sustainability must be the main

objective of these patients’ rehabilitation.30 Autografts are considered to be the gold standard

for management for these type of defects.31 But

there are associated problems with its use such

as selecting a suitable donor site, the morbidity of the donor site, especially for larger defects,

complications associated with tissue harvesting,

the discomfort of the patient, potential for infection both at the recipient’s and donor’s sites, the

additional skilled surgical team required, prolonged surgical time, and graft resorption. Due

to these restrictions, research is still being done

to find an appropriate alloplastic material and

accurate presurgical planning is needed to enhance craniofacial reconstruction.32

For mandibular defects, locking reconstruction

plates are advised to be used; however, these

plates must be properly bent to achieve the proper

mandibular contour. Preoperative plate bending

using three-dimensional (3D) stereolithographic models is becoming more and more popular

among surgeons.33 Engineering patient-specific

designs whose performance can be accurately

and precisely predicted will assist surgeons in

their routine procedures. The ability to precisely plan preoperatively, carry out virtual osteotomies or resections, and design patient-specific

implants are all facilitated by computer-assisted designing and manufacturing systems. Because of this cutting-edge technology, it is now

possible to create patient-specific implants using virtual designs and models.34 The advent of

computer-assisted design and manufacturing

techniques for maxillofacial reconstruction has

significantly improved surgical success since the

length and form of the implant may be customized to the needs of the patient and the surgeon’s

preferences.32, 35

Taking the entire stomatognathic system into

overview in both mandibular guidance therapy

as well as maxillectomy/midfacial defects classified as per the extent of resection, requires a

multidisciplinary approach viz. prosthetic (guidance prosthesis, inclined plane prosthesis), via

splints, IMF, grafts, obturators, etc. To provide the best treatment, one must employ a philosophic approach that would concentrate on selecting the most suitable material and technique

along with a good physiotherapy regimen for an

overall successful and positive rehabilitation experience.